Technology & Society

27 Social Media Use Is a Form of Dissociation, Not Addiction

Amanda Baughan

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, I had an unfortunate Saturday routine. I would wake up in my studio apartment and immediately turn to my phone, telling myself that I would get breakfast after quickly checking Twitter.

An hour or so later, I would look up and realize what time it was – and how ravenous I’d become. I had become totally absorbed in looking at memes, snark and the 24 hour news cycle.

This experience sparked an idea: What if, instead of people becoming “addicted” to social media – as users often characterize their excessive engagement – they’re actually dissociating, or becoming so engaged that they lose track of time?

I’ve researched people’s social media use for four years as a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington, and my collaborators and I decided to design a study to test this theory.

What is dissociation?

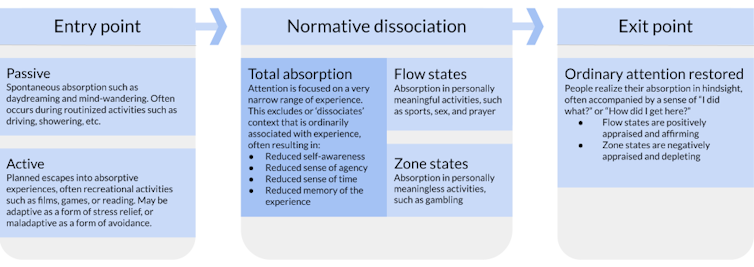

Many researchers think dissociation occurs on a spectrum. On one end, there is the kind of dissociation that is spurred by trauma and associated with PTSD flashbacks.

Then there are common, everyday experiences of dissociation, which involve attention being limited to a narrow range of experience. Everyday dissociation can be passive or active. Spontaneous daydreaming is a form of passive dissociation, while reading a book is an example of active dissociation. In both cases, you can become so immersed in a fantasy or story that time falls away and you lose track of your surroundings. You might not be able to hear someone calling your name from another room.

Dissociation is part of healthy cognitive functioning, as mind-wandering helps you learn, and combating stress though deeply engaging in hobbies can boost your mood.

What does dissociation look like online?

When online, however, dissociation can reflect zombie-like behavior – scrolling for hours without realizing it, not being aware to one’s surroundings while scrolling, or scrolling on autopilot and then realizing you haven’t actually paid any attention to what you’ve read. Have you ever seen someone so absorbed in their phone that they start walking across a street, oblivious to oncoming traffic? They’re likely dissociating.

Typically, behavior like this is classified as smartphone or internet addiction.

However, researchers have begun to push back against the narrative of addiction to describe excessive smartphone use, explaining that the behavior – even if it’s a source of distress – should not be considered addiction if it’s better explained by an underlying disorder, is a willful choice, or is part of a coping strategy.

I am of the belief that choosing to play Candy Crush for three hours a day is not necessarily “addiction.” I do, however, think that the complete disconnect people experience from their surroundings and sense of time passing is an interesting phenomenon to explore. Therefore, I wanted to understand if people are dissociating during their phone use.

In our study, we recruited volunteers to use a custom mobile app alternative to Twitter, called Chirp. Forty-three people used Chirp for four weeks, cycling through four different design interventions, coupled with in-app surveys. We then selected 11 of them to interview about the experience.

We found dissociation occurred in nearly half of our participants, and they often expressed a sense of disappointment afterwards, saying that they would have rather have engaged in a different activity with the amount of time they had spent online. However, some said their time on social media was meaningful to them, and the fact that they were connecting with real people was valuable, even as they dissociated.

Cultivating online agency

Understanding social media overuse as a byproduct of dissociation, rather than addiction, can help destigmatize social media use while empowering users. This framing also helps explain why social media sits in a paradoxical position: people have frustrating relationships with social media platforms that they are simultaneously unwilling to quit.

Seeking escape from the present moment through deep absorption – including absorption in social media – is a natural, common, and often beneficial thing to do. However, when users spend much more time dissociating online than they would have consciously chosen for themselves, they become frustrated and conflicted. And many social media platforms exploit this tendency by keeping people “on the hunt” for new content through algorithmic design.

This suggests that it is possible for users to have healthy and satisfying relationships with social media – even when dissociating is involved – if the platforms can also help their users disengage.

How design can reduce dissociation

In our study, we deployed several interventions to help pause or reduce dissociation while scrolling on Chirp. One intervention that was particularly effective was requiring our participants to sort their content into lists by topic – say, news, sports and reality TV – rather than having all subjects appear as an avalanche of information on one main feed. People could then click different tabs to view their lists. We found that many users would only scroll through one or two tabs before exiting the app.

We paired this intervention with a “reading history” label that informed our users when they were “all caught up” with previously viewed tweets. Participants said that this helped them feel more in control and less likely to lose track of time.

Of course, many current social media companies, such as TikTok, rely on algorithmically-determined, constantly updating content. Similarly, on Instagram and Twitter, popular and trending content gets inserted into a feed of followed content. This makes it impossible to ever get “all caught up.”

In these cases, past research shows that many people would appreciate reminders to log off before 30 minutes of use. Otherwise they become disappointed with the time they’ve spent. These reminders could be inserted into regular content, which is something TikTok already does.

Users can do this for themselves by becoming familiar with the suite of digital well-being tools at their disposal. Viewing usage page statistics and setting timeouts is already available across many sites, although many of these settings are turned off by default.

However when more people use these tools, it signals to the companies that they should continue to invest time and resources into developing them.

Amanda Baughan, PhD Student in Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()